It’s January 2026. You open your notes app or your planner and think “Okay. This year I’m doing it properly.” You map out mornings and set big goals. You promise yourself structure, consistency, a routine that finally sticks. For a few days, maybe even a couple of weeks, it works. Then life interrupts. You sleep in once. You miss a task. You get overwhelmed. One skipped day turns into two. Two turns into “I’ll start again on Monday.” And suddenly the routine you were excited about feels heavy, distant, and hard to return to.

If you’re neurodivergent, this moment hits harder. Your brain jumps straight to all-or-nothing thinking. I’ve already ruined it. What’s the point now? Here’s what rarely gets said: this isn’t a failure. It’s a completely normal pattern. Big New Year goals often don’t leave room for flexibility as they don’t expect routines to break. What matters isn’t whether you fall off your routine. It’s how gently you let yourself get back on. Not by starting from scratch or punishing yourself. But by rebuilding in a way that actually works with your brain.

The article explores why routines fall apart more easily for neurodivergent brains, why “starting fresh” often makes things worse, and how rebuilding gently in 2026 leads to more sustainable productivity.

30 day money back guarantee

No Credit Card Required Upfront

Defining the New Year Routine Crash

The New Year Routine Crash refers to the sudden breakdown of routines shortly after the start of the year. It often happens when ambitious plans meet real life, fluctuating energy levels, or cognitive overload.

Habit formation research shows that routines don’t become automatic straight away. They need repeated practice in stable, predictable situations, often over weeks or even months. If a routine breaks early on, it doesn’t mean it failed — it just means the habit hadn’t had time to settle yet. For neurodivergent people, routines built too quickly or with too much pressure can become overwhelming, making them harder to return to when energy or focus drops.

How Does the New Year Routine Crash Relate to ADHD?

For neurodivergent people, routines often break more easily — not because of a lack of effort, but because routines place heavy demands on parts of the brain that already work harder day to day. Differences in executive functioning, motivation, and how progress is interpreted can make New Year routines especially fragile.

1. Executive Function Load

Executive functions are the mental skills that help us plan, organise, remember steps, and start tasks. These skills are essential for keeping routines going — and research shows this is harder for people with ADHD (Kofler et al., 2024). This means that routines that require planning and organisation feel harder to maintain by default because they rely heavily on brain processes that already work overtime.

When New Year routines rely on strict schedules, constant self tracking, or doing many things “on time,” they can quickly become draining. Even if the motivation to do those activities are there, the mental effort required to make sure everything runs smoothly can be exhausting.

2. Cognitive Overload and Planning Fatigue

Our brains can only handle so much at once. Cognitive load theory explains that performance declines when too many mental demands pile up (Sweller, 1988). This is not because we don’t want to do the thing, but because the brain is overwhelmed.

At the start of the year, routines change all at once from new habits, new tools, new goals, and many new expectations. For neurodivergent people, this can quickly tip into overload. When this happens, the brain might respond by avoiding tasks, shutting down or disconnecting. This is not because of laziness but a way to deal with being exhausted mentally.

3. All-or-Nothing Thinking

For many neurodivergent people, even a small change in routine can feel much bigger than it is. Doing just one thing that is ‘out of order’ can be understood as the whole routine has fallen apart. This pattern is often described as all-or-nothing (dichotomous) thinking where experiences are interpreted in extreme opposites (e.g., success vs failure) without much room for middle ground (American Psychological Association, 2018).

People with ADHD can be especially affected by this because flexibility and emotional regulation can become harder when plans don’t go as expected. When something goes off track, the brain may jump straight to “I’ve failed”, even if most of the routine is still intact.

This shows up often in informal ADHD peer communities, where people describe feeling “frozen” after even small routine changes. As one community member put it:

“Whenever a routine is disrupted, I feel frozen… It takes a lot of energy to do something a different way.”

Anonymous online community post (details removed).

When routines are treated as ‘fragile’ coming back to them can feel harder than starting from scratch. That’s why this kind of thinking doesn’t just affect how a setback feels — it can make restarting much less likely, even when a gentle return would actually help.

4. Impact on Motivation and Task Persistence

Motivation isn’t just about wanting to do something. — it’s also about being able to keep going over time even if things aren’t perfect. People with ADHD often experience differences in task persistence, even if the goal genuinely matters to them.

One study of university students found that ADHD symptoms were linked with lower self-efficacy, meaning students were less likely to believe they could handle challenges as they came up. This lower confidence was connected to outcomes like higher dropout intention and difficulties adapting to demands (Müller et al., 2024).

Other research suggests that motivation in ADHD is more complex than effort alone. It’s closely tied to how the brain processes reward, feedback, and internal drive, rather than simply how much someone “wants it” (Morsink et al., 2022).

Put together, this helps explain why routines can feel harder to return to after a disruption. When something goes off track, people with ADHD may lose confidence in their ability to keep going not because they don’t care, but because their brains respond to setbacks differently. This makes persistence after early disruptions more difficult, even when the desire to improve is still there.

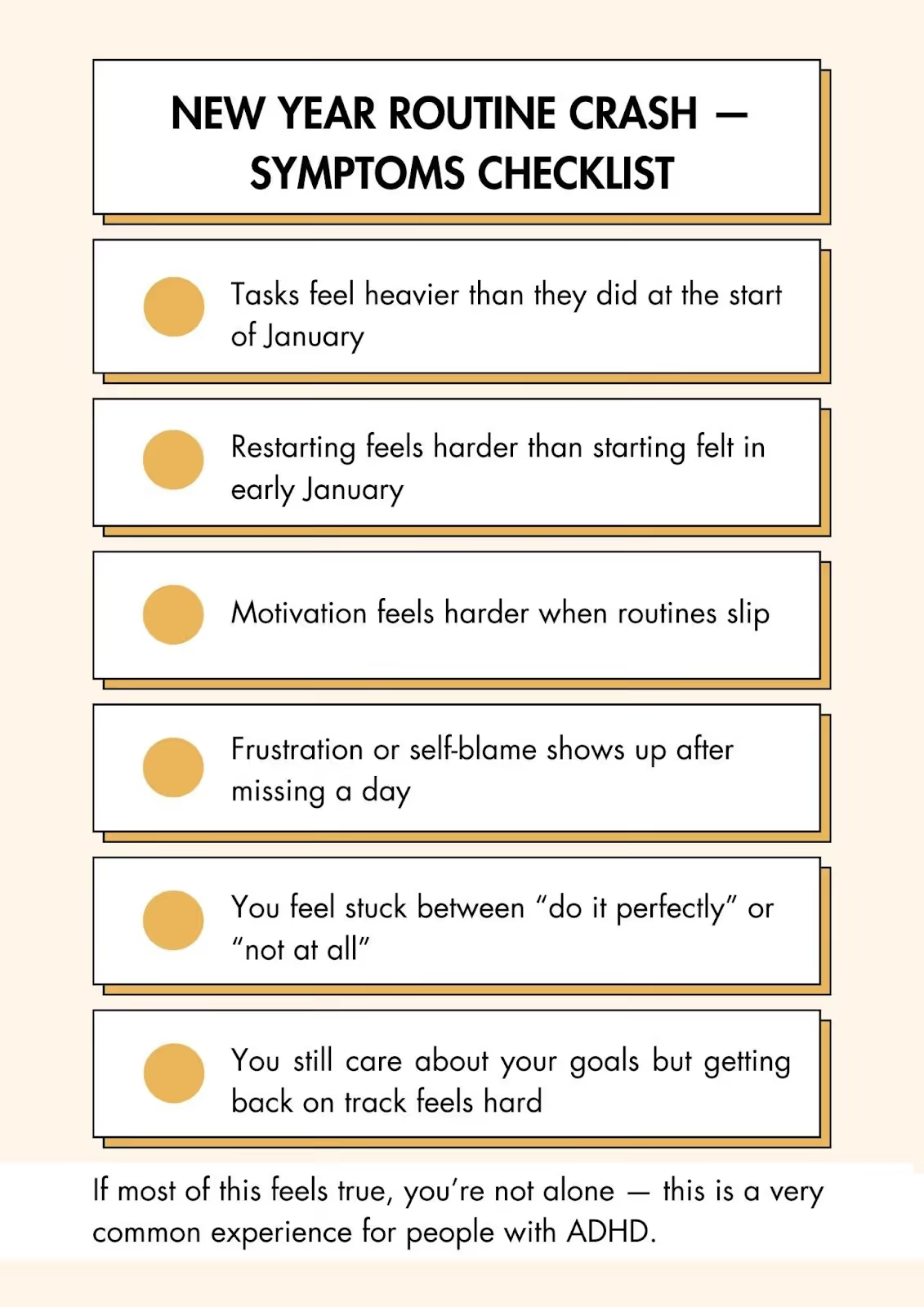

Symptoms of the New Year Routine Crash

Research shows that people tend to give up on New Year Resolutions within the first month if their goals are rigid, vague, or lack flexibility as well as how sticking with resolutions requires them to be adaptable and have constant motivation over time (Dickson et al., 2021).

If you’re experiencing a New Year routine crash, you may notice some of the following signs:

1. Loss of motivation

At the beginning of January 2026, fresh routines and resolutions felt exciting and manageable. But for many people this motivation tends to fade after the first few weeks even when they still care about the goal. Research shows that this drop is very common with many people struggling to sustain resolutions over time (Oscarsson et al., 2020).

For people with ADHD, this drop in motivation can feel stronger and more discouraging. ADHD is linked with differences in how motivation works over time, particularly when tasks require sustained effort without immediate reward. Research suggests that motivation in ADHD is closely tied to whether tasks feel meaningful, manageable, and rewarding in the short term (Morsink et al., 2022). When routines start to feel effortful without clear payoff, motivation can drop quickly.

2. Difficulty restarting tasks

Restarting feels harder than starting did in January, with only 9% of people being able to successfully keep their New Year resolutions (Batts, 2023).

This matches what we hear in the neurodivergent community: once a routine breaks, the activation energy needed to re-enter can feel much higher than launching it in the first place.

3. Increased mental fatigue

Even when tasks aren’t physically demanding, keeping routines going can be mentally exhausting. Maintaining habits requires ongoing planning, attention, and self-monitoring, and that effort builds up over time.

For neurodivergent people, this mental fatigue can show up faster. Tasks that involve organising, managing time, or staying focused often require more conscious effort rather than happening automatically. As a result, routines can feel draining to maintain, making it easier to run out of mental energy and fall off — especially after disruptions or busy periods.

4. Irritability

Irritability is a common sign of a New Year routine crash, especially as the structure and novelty of early January fades.

People with ADHD often find that symptoms like irritability worsen when daily structure breaks down, even during times that are supposed to feel enjoyable or motivating. A similar pattern can show up after New Year routines start to slip: expectations stay high, structure drops, and frustration increases.

Its normal to feel disappointed when you really wanted to follow through, and for neurodivergent people this gap can feel especially personal.

Below is a visual summary of these experiences. Use it as a gentle check-in if that feels helpful.

Rethinking New Year Resolutions: What Works Better for ADHD

1. Lower the starting point of the resolution with one tiny repeatable action

Big vague resolutions (like “be more productive” and “be healthier”) often fail because they require consistent planning, organisation, and follow-through. Breaking goals into small doable steps and building routines that are realistic to repeat.

Example:

Instead of “be healthier,” start with:

→ Drink a glass of water after waking up

→ Go for a 5 minute walk around the block

→ Eat one piece of fruit during the day

→ Stretch for 30 seconds

Instead of “have a better morning routine,” start with:

→ Sit up in bed instead of scrolling

→ Open the curtains

→ Do your skincare routine

→ Make your bed

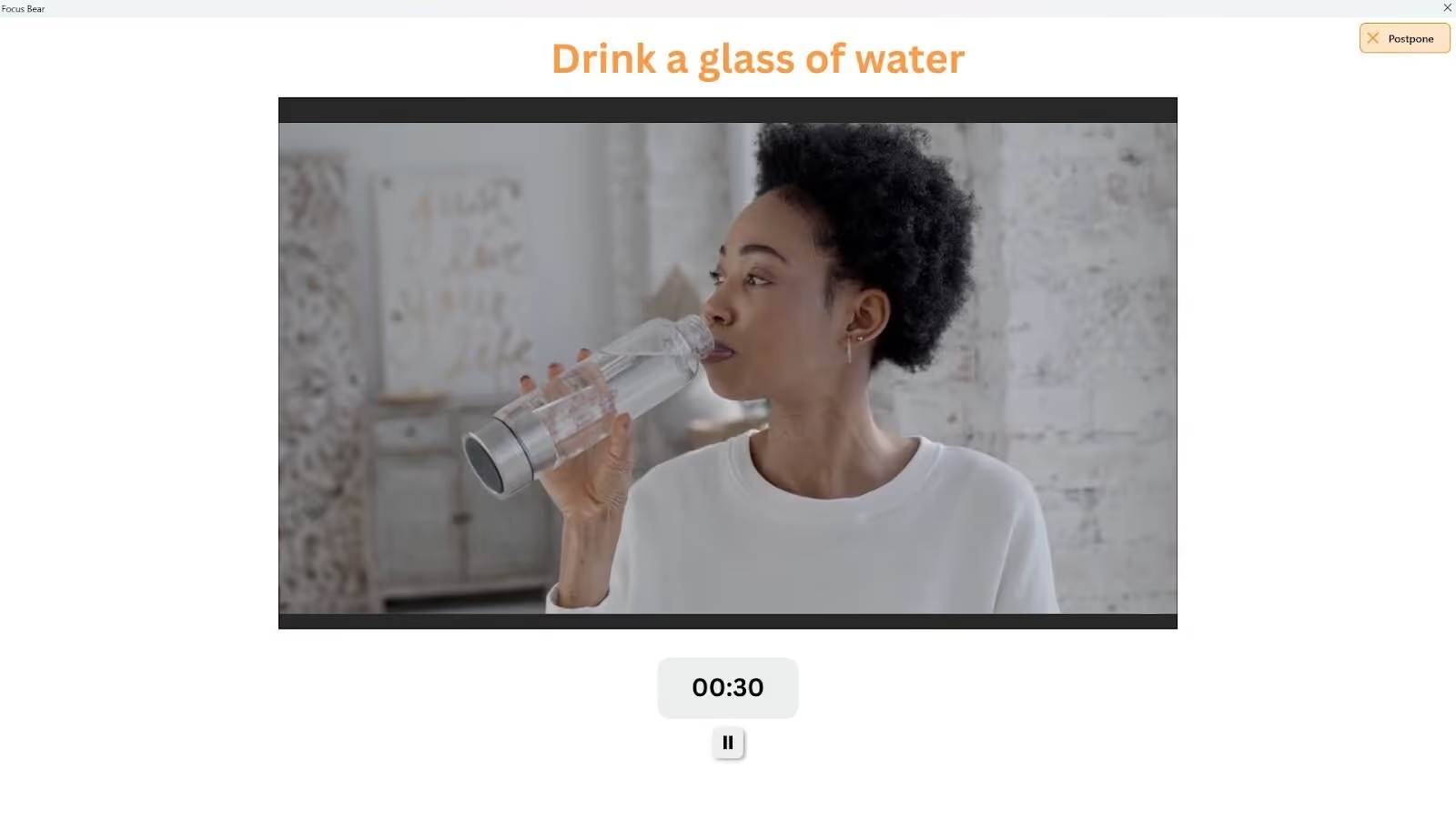

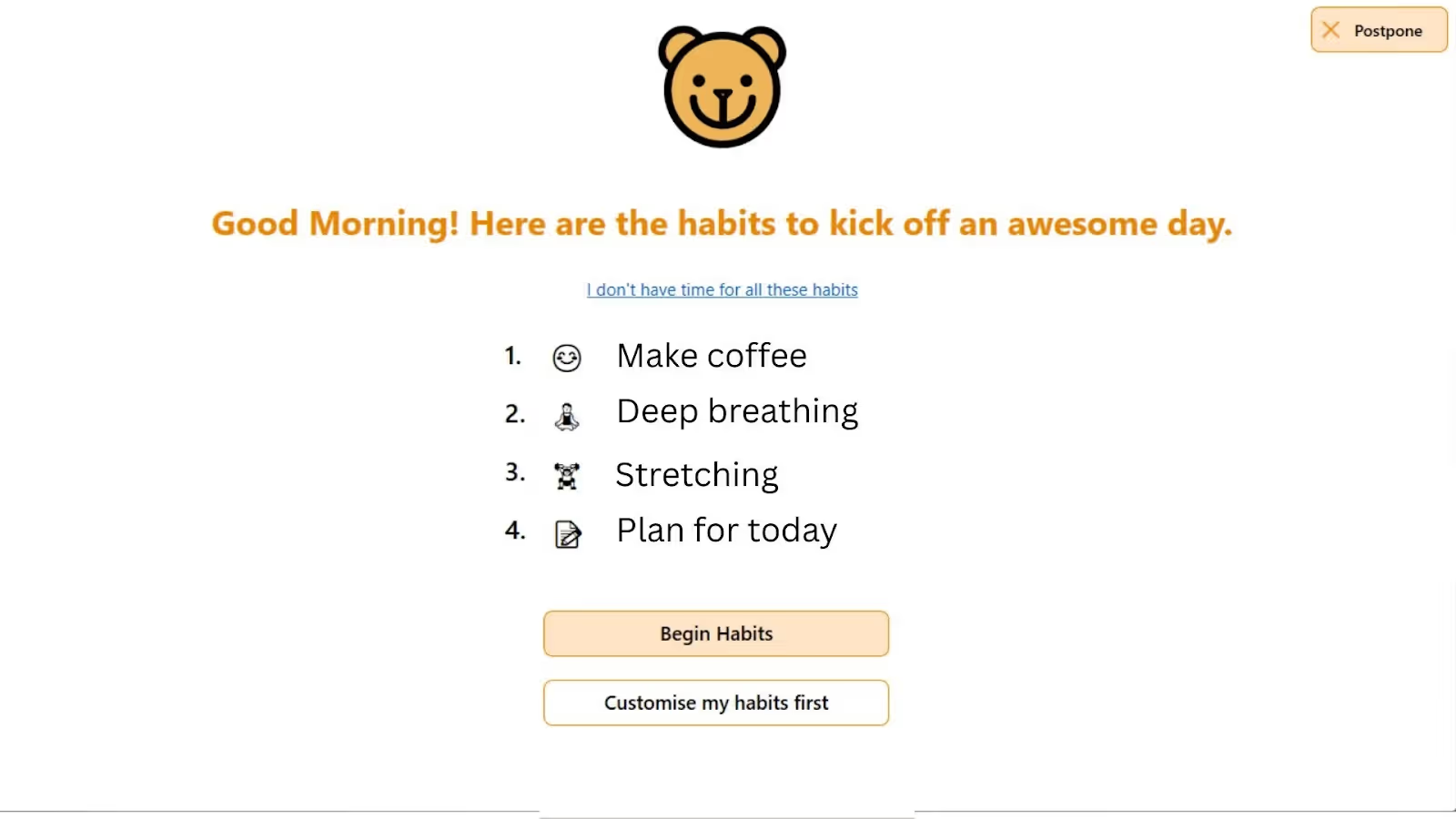

Tools like Focus Bear can help by turning these tiny actions into guided routines. Instead of relying on memory or motivation, the app prompts one step at a time (for example, “drink a glass of water”) making it easier to start and repeat without feeling overwhelmed.

2. Attach new habits to something you already do

Habits are often easier to keep when they’re attached to existing routines, rather than being brand new tasks. This works because it lowers the mental effort needed to remember and start.

Example: Instead of “meditate every morning,” try:

→ After I make coffee, I do one short breathing exercise.

Focus Bear lets you schedule habits alongside existing actions, like pairing a grounding exercise with your morning check-in or a focus session after lunch. This makes routines feel more natural and less forced.

3. Design routines you can return to

Willpower-based routines tend to collapse quickly not because people don’t care, but because life, energy, and attention fluctuate. What helps is designing routines that expect missed days and making restarting feel safe, not shameful.

Instead of “I missed my workout yesterday. I’ve failed.” shift to:

→ “I’ll restart today with 10 squats or a 5 minute walk”

Instead of “I didn’t study yesterday, there’s no point now” shift to:

→ “I’ll open my notes and revise for 5 minutes”

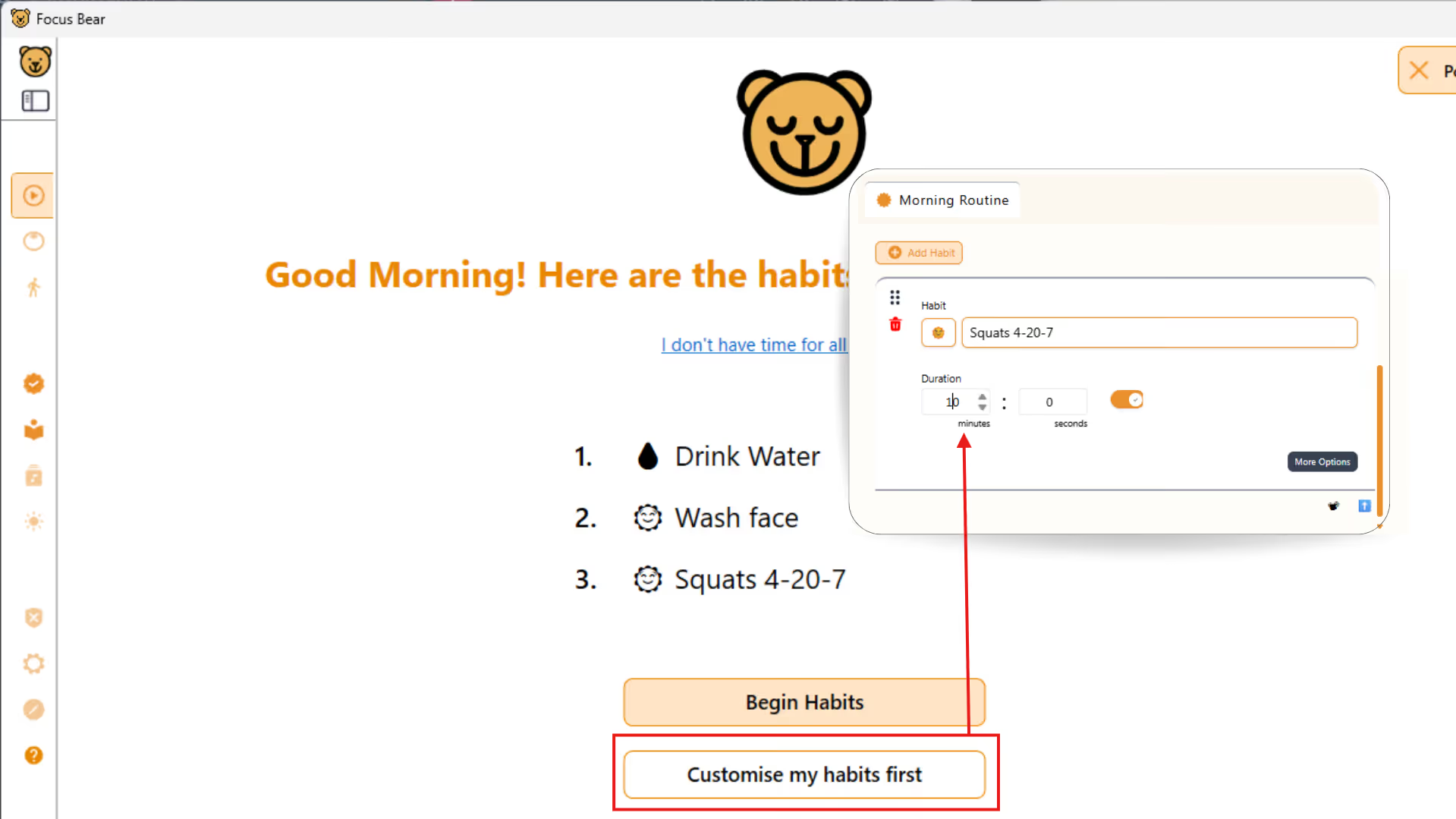

Focus Bear allows users to customise the intensity and duration of each habit at any time, making routines adaptable to daily changes in mood or energy. This helps in making users stay consistent without guilt and makes routines easier to return to over time.

Falling Off Isn’t Failure

If your New Year resolutions have already started to slip, it doesn’t mean you failed — it means your routines were built for an ideal version of life, not the real one. For people with ADHD and other neurodivergent brains, routines are more likely to break when they rely on willpower, rigid expectations, or all-or-nothing thinking. What actually matters is not staying perfectly consistent, but having a way to return when things fall apart.

Rebuilding routines in 2026 doesn’t need to involve starting over or pushing harder. It works better when goals are smaller, habits are attached to what you already do, and routines are flexible enough to adapt to changing energy and focus. Progress can look like drinking a glass of water, writing one sentence, or showing up for five minutes — and that still counts. Falling off your routine isn’t the end of the story. The ability to come back, gently and without guilt, is what makes routines sustainable in the long run.